“It is possible, with lots of hard work, dedication, and timely help, to make a good writer out of a merely competent one,” writes Stephen King in On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft. I believe the same applies to web writers.

Many of us have intuited some of the principles of web writing, often from years of writing and reading online. But it was formal training—via Higher Ed Experts’ Web Writing for Higher Ed course—that made me the bona fide web writer I am today. The four-week online course, then taught by Michael Powers, gave me the knowledge, skills, and credentials to write and edit content specifically for the web. I now teach the course, which we’re constantly updating with the latest research, articles, advice, and best practices on the subject.

As part of the class, we use some online tools to help assess our web writing. To be clear: There are no magic shortcuts to becoming a good web writer! It takes “hard work, dedication, and timely help,” as King notes. Still, I’d be remiss not to recommend adding one or two of these online resources to your web writing toolkit.

Assess Readability

Readability is a fundamental principle of web writing, one that contributes to the usability and accessibility of your content.

Lots of online tools can assess the readability of your web content. In the web writing course I teach, we use the Readability Test Tool. It offers an aggregate readability score based on the most-used readability indices, including Flesch-Kincaid’s measures of grade level and reading ease.

In general, I advocate for plain language on the web. After all, what good is web content if your audience can’t read it, use it, and then act on it? Higher education websites, however, represent a special challenge for web writers because they serve a range of audiences, both internal and external.

As a result, there’s probably no one, single readability grade level or score that’s appropriate for your entire web communications strategy. For each web page or piece of content, consider both the format and the audience. A PhD program’s overview page for prospective graduate students will differ in its readability score from an email fundraising appeal targeting your institution’s alumni. You’re going to use different words to achieve different goals, so adjust your targeted readability scores accordingly. The good news? Using web writing tactics and techniques often leads to better readability scores.

Analyze Style

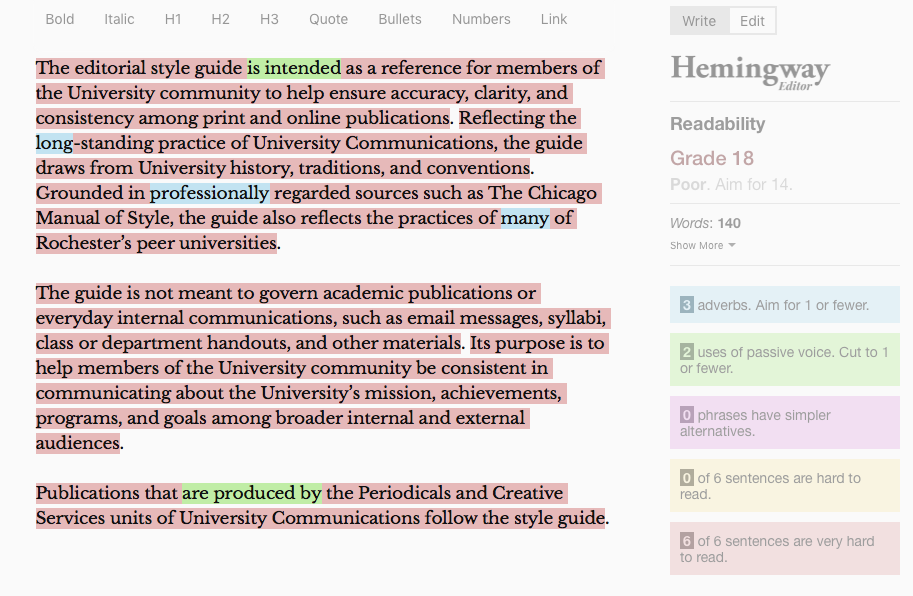

Your college or university may have an in-house style guide. At the University of Rochester, our editorial style guide is based on The Chicago Manual of Style. It prioritizes clarity and includes a note about tone that reads, “We want to be clear, direct, authentic, intelligent, confident, and at times, personal.”

For kicks, I ran the first three paragraphs of our style guide through the updated version of the Hemingway Editor, a free online app that bills itself as being “like a spellchecker, but for style.” In addition to reporting the word count and readability score, the app identifies:

- Adverbs (the road to hell is paved with them, per King)

- Instances of the passive voice

- Phrases with simpler alternatives

The results were illuminating. Take a look:

Our style guide is “for members of the University community,” yet the readability score comes in at grade level 18! That’s something to address, not least because departmental administrators and student workers help create and manage web content. You shouldn’t need an advanced degree to read an online style guide. Even if you have an advanced degree, you probably don’t want to spend extra time parsing an institution’s style guide.

Want to delve deeper into style analysis? Try Expresso, a free app that identifies additional style issues in your writing such as:

- Weak verbs—Overused vague words, a common mistake I see in web writing.

- Filler words—Often unnecessary words, such as really, very, just, literally, etc. Heed editor William Allen White’s advice, as documented in a Seattle newspaper from 1935: “If you feel the urge of ‘very’ coming on, just write the word, ‘damn,’ in the place of ‘very.’ The editor will strike out the word, ‘damn,’ and you will have a good sentence.”

- Rare words—The app defines these as not being among the 5,000 most frequently used English words.

- Nominalizations—Turning a verb, adjective, or adverb into a noun (e.g., decision is a nominalization of decide).

For writers, style guides offer clarity, authority, and reassurance in our ever-changing world of words. Style-assessing online tools, meanwhile, can help keep our writing tics in check. That said, all guides and tools should incorporate flexibility to reflect the realities of writing in a digital age. As always, keep your audience and the format top of mind!

Check Spelling and Grammar

It goes without saying that spelling and grammar are basic components of writing. But even professional writers make mistakes. There are some words I struggle to spell correctly (I’m looking at you, cemetery) and grammar rules I can’t commit to memory (lay versus lie, my albatross).

It goes without saying that spelling and grammar are basic components of writing. But even professional writers make mistakes. There are some words I struggle to spell correctly (I’m looking at you, cemetery) and grammar rules I can’t commit to memory (lay versus lie, my albatross).

Fortunately, there’s Grammarly, a web app and plugin. It’s an online proofreading tool that checks your text for grammar, punctuation, and style, and features a contextual spell checker (for when you use the wrong word, but spell it correctly) and plagiarism detector. I like it because it works on social media platforms and content management systems, and it offers corrections along with explanations.

The free version includes Weekly Grammarly Insights that are emailed to you. This is mainly an upsell attempt, but it’s fun (yes, fun!) because it reports on your activity, mastery, vocabulary, and top grammar mistakes.

Evaluate Tone and Emotion

I wrote a bit about tone in the style section, but it warrants additional commentary because I discovered ToneCheck, or “emotional spellcheck for email.” (FWIW, Grammarly wants me to replace spellcheck with spell check, while The New York Times uses spell-check).

Social neuroscience research suggests there’s a negativity bias in digital communication, such as email.  “What you thought was a neutral message can be perceived as hostile by the recipient,” according to psychologist and author David Goleman. I’ve often suspected as much, which is why I’ll have a friend or colleague read over my draft before I send an important email. Other recent research indicates that ending text messages with a period can make you seem angry and insincere to the recipient.

“What you thought was a neutral message can be perceived as hostile by the recipient,” according to psychologist and author David Goleman. I’ve often suspected as much, which is why I’ll have a friend or colleague read over my draft before I send an important email. Other recent research indicates that ending text messages with a period can make you seem angry and insincere to the recipient.

Conveying the right tone and emotion is more difficult when you have a limited word count, which is why writing a compelling headline or subject line is its own skill. The Advanced Marketing Institute’s Emotional Marketing Value Headline Analyzer is a free tool that evaluates how emotional your headlines are. In a world where fewer people are reading beyond clickbait headlines and subject lines, writers have to be thoughtful about the emotions their words prompt in readers. This tool lets you test various versions of your headline to determine which emotion you want to target.

Where words and excessive exclamation points fail, I think emoji, Bitmoji, GIFs, and images can succeed. This is true with social media and text messages, but also works in emails and blog posts, don’t you think?!

Test Displays

In Higher Ed Experts’ web writing course, we learn how users read on the web while keeping in mind how they access our content, from desktop computers to mobile devices.

One of my colleagues at Rochester introduced me to a nifty free tool called Screenfly. You enter a URL and it shows you what that page looks like on specific monitors, tablets, smartphones, and other devices. You can even enter custom screen sizes.

Responsive design helps address some of the challenges created by variations in screen sizes. For me, the value of a tool like Screenfly comes in demonstrating to faculty and staff how daunting their impenetrable walls of text can be to readers. Those of us who work on a desktop computer with two (or more) monitors can forget that some of our audiences may be accessing our content primarily via smartphone or screenreader.

Go beyond online tools

Technology is a tool, not a cure-all. If you want to improve your writing—for the web or otherwise—that generally means lots of reading and writing, as well as practice, practice, practice, something we do a lot of in the web writing course I teach.

My advice? Avoid getting bogged down using online tools all the time. Stephen King says it best: “If you don’t have time to read, you don’t have the time (or the tools) to write. Simple as that.”

Have you used any good online tools to improve your writing? Let me know in the comments.

Meet the Faculty: Sofia Tokar

Higher Ed Experts is a professional online school for digital professionals working in universities and colleges.

When you take a professional certificate course with us, you get a chance to upgrade your skills by working on your projects, interacting with classmates just like you and getting detailed personalized feedback from your instructor.

Sofia Tokar Sofia is the web writer and communications officer for Arts, Sciences and Engineering at the University of Rochester. As part of the web team, her work includes creating, editing, and curating content for the university’s homepage and top-level pages, departmental web pages, and social media accounts. She regularly co-hosts on-campus presentations and workshops about strategic and tactical web communications.

Sofia Tokar Sofia is the web writer and communications officer for Arts, Sciences and Engineering at the University of Rochester. As part of the web team, her work includes creating, editing, and curating content for the university’s homepage and top-level pages, departmental web pages, and social media accounts. She regularly co-hosts on-campus presentations and workshops about strategic and tactical web communications.

Sofia earned her master’s degree in English language and literature from Queen’s University in Canada. She is currently pursuing her master’s in online teaching and learning at UR. She is also a graduate of the Higher Ed Experts web writing certificate program.

Sofia teaches Higher Ed Expert’s 4-week online course on Web Writing for Higher Education.

Tags: Higher Ed Experts Faculty, Higher Ed News